This is where my story becomes a lot less ‘solo’, and a lot more German. After the night buses and painful 12-hour wait sleeping on the floor of Bogota’s airport, and after the tantalising flight and Uber ride on the other side in San Jose, which dragged on and yet went too quickly, I couldn’t decide, I stood outside the hostel where I knew Paul and Lukas had booked us beds, and hesitated. I’d done a lot of scary things in the last four months, but this pretty much topped it. I was nervous as shit. This was it. I was about to start travelling with two German boys who, if I’m completely honest, I barely even knew, and one of whom I’d managed to fall in love with. We’d not even spent two weeks together collectively, and yet here I was. I’d missed a flight home for this, I’d convinced myself that I’d never been so sure of a decision in my life, and even so, I was terrified. What if things were different now we’d left Puerto Viejo? There was one way to find out. I pushed the gate open and rang the hostel doorbell.

Needless to say, Paul and Lukas were just as cool as they’d been in Puerto Viejo, and we were still as good of a team as we were back then. Upon seeing their faces I practically jumped into their arms, abandoning all bags and leaving a bewildered hostel staff member at the reception desk. Immediately, we resumed our calm Caribbean ways and went on a group shop, labelling everything, bananas, bottles and bread, with our initials ‘LCP’, and cooking a massive vegetarian dinner. The hostel we were staying in, aptly named ‘Relax’, was to become our favourite San Jose hang-out spot to date, with its ultra chill stoner staff members, free American pancake breakfasts, and absolutely tiny bunk-beds that only added to the vibe. We spent a couple of days whizzing around Costa Rica’s capital city preparing for our trip to Nicaragua, doing PCR tests, printing documents, and buying goods that we wouldn’t have access to on the rural Pacific side for a long time, and then suddenly we were off again. On the road.

And thus began our month-long journey of ups and downs, huge highs and mega lows, scams and surf. I won’t go through everything considering it wasn’t very solo of me, my own special little journey ending at Bogota airport a few days prior, but some details are too gold to miss.

Our first challenge, which obviously went wrong, was getting all the way from San Jose to Popoyo, Nicaragua’s most famous surf town that I hadn’t been to before, in a single day. That meant two buses on the Costa Rican side, a border crossing, and two chicken buses on the Nicaraguan side. As expected, with Costa Rica being the land of true pura vida and shit public transport, and after a child legitimately peed through the seat in front of us on a local bus towards the border, resulting in all three of us gripping our bags and knees to our chests and watching the urine slide around the bus floor in a horribly long trail, it didn’t work out. We got to the border far too late for anything, and barely even made it through considering most of the offices were shut. Forever in good spirits, though, and still laughing at the pissing child on the bus, Lukas managed to secure us a taxi to the nearest town, Rivas, and a place to sleep there for the night. This was the first time of many we had to navigate fitting three full-grown adults and a six-foot surfboard into a small saloon car, and each time we wriggled into our jigsaw places curved around the board crossing the entire length of the taxi, it didn’t get any less funny.

Rivas, the southern Nicaraguan hub for chicken buses and markets, is a crazy bustle of local life, and even though I’d visited before, I was still in awe of its rawness. With two men, I found myself able to do things I never would’ve before, like checking into the sketchiest local motel in town and grabbing breakfast in the heart of the town’s mercado maze, being served by utterly confused locals watching us scoff down our rice and beans and platanos. Paul and Lukas had never taken a chicken bus before, so it was my honour, pleasure, to introduce them to the wildest mode of transport in all of Central America, the old yellow school buses-turned death contraptions that could fit an entire community, all their animals, and a few ice cream carts inside. Being back in Central America felt like returning home, like entering dream-world again after the sincerity of Colombia; here, everything was hilarious, unbelievable, strange in the best way. And Nicaragua was a whopper place to start, being much less westernised than Costa Rica and much more chaotic in every single way.

We sat at Rivas’ chicken bus station, the most interesting jumble of blossoming life I’ve ever seen, for half an hour before starting towards Popoyo, just watching: Sellers calling out their goods and prices, children squealing and running, people throwing each other bags of weird snacks and cold Fanta bottles, chicken bus conductors yelling their destination over and over again until the words became blurred with one another, completely incomprehensible. The boys were in a state of shock, and me in a state of sheer pride; they’d never seen anything quite like it, and I was the one showing them. The crew operating our chicken bus to Popoyo decided they were in love with me, and I decided to start a proposal count, which was already on at least two after our stint mixing with locals in Rivas. The leader of the group regretfully waved me goodbye as we hopped off, blowing kisses as they quite literally left us in the dust, our ‘bus stop’ being more like ‘in the middle of nowhere’.

The week we spent in Popoyo reminded me just how intense Nicaragua’s dry season can be, just how sweltering and exhausting it is. After leaving the boys’ extensive arsenal of food for cooking on the top of the chicken bus, our days were spent hitch-hiking to the nearest ATMs and supermarkets for any hope of buying goods cheaper than the extortionate tourist prices in Popoyo, and for me, fending off yet more proposals from white van drivers while Lukas got thrown around in the back. Paul stayed and surfed a lot, and we occasionally joined him, but before long the temptation to return to our hostel, relax, make dinner, and soak in the dying sun after its lingering midday heat, overtook all of our ambitions. We met a group of backpackers, which included the most terrifying small woman I’ve ever crossed paths with, and who we spent the whole week trying to dodge. A trained doctor, who seemed to be simultaneously a gynaecologist, geneticist, surgeon and dermatologist, based on her loud claims to let the entire town know, she spent her time talking AT us rather than to us, telling us we would get skin cancer and barging in on me in the toilet and watching me piss. After ten unbearable minutes during one group dinner of listening to her heated inner monologue about how underestimated she is in the medical world, I hissed to Lukas out of the corner of mouth, “We have to swap, she’s sucking my soul dry.” He pouted and tried to protest, but seeing me on the verge of breaking down, engaged the tiny scary woman in conversation and flinched as she launched into a new speech.

Saturday came, and Sunday Funday in San Juan, one of my favourite Central American parties, called – as did Challis, my gorgeous American friend who I volunteered with in Guatemala, and who had finally made it down to Nicaragua only to settle on the island of Ometepe, vowing to never leave aside from partying in San Juan. Paul, Lukas and I narrowly caught the last chicken bus of the day, hitch-hiking back to the dusty bus stop signified only by a tortilla stand, and after the initial mad rush of throwing ourselves and our bags on the back, the entire crew paused, as did we, as we realised we knew each other. It was the exact same team who brought us here, and with an outcry of joy, the man who proposed to me guided me to a seat and commanded a couple of the boys to pick up some beers from a local tienda. The entire ride back to Rivas turned into a rural beer crawl, with the chicken bus stopping abruptly every ten minutes at a new shop, someone running to grab beers that were ready and waiting at the door, and launching them back inside for our group to celebrate with. I gingerly told my admirer that I was actually with Paul, and he promised the German boys that he wouldn’t take me away and marry me, as if, otherwise, it would’ve been a reasonable course of action.

I reunited with Challis in San Juan, who’d managed to misplace her phone and was now armed with possibly the worst excuse for a smartphone I’d ever seen. Together with her friend Fanny, a volunteer at Challis’ hostel in Ometepe that she had basically claimed as her home, the five of us became Guacamole, with each person’s code name being an ingredient in case we got lost in the party town. We snuck into Sunday Funday and consequently got chased around the pool by an angry security woman wanting to make us pay, and travelled from hostel to hostel via pick-ups and chicken buses, slowly getting more and more intoxicated and wild as the night ensued. After Challis left town, the boys and I spent a few groggy days trying to recover from a seemingly permanent hangover, noticing how asleep San Juan became during the week, how slow and stuck it felt to trudge around the streets, as if dragging ourselves through mud.

Finally, an open-mic night at a local bar awoke us from our joint slumber, and we met Ewald, a German rapper who could freestyle from English to German to Russian in the space of a single breath. I’ve never witnessed a mind working quite like his does, the beautiful, spiritual and wise thoughts it comes out with, and for a heavenly ten minutes, he and Lukas jammed together, Lukas being able to pick up a new beat every few verses on the guitar to match Ewald’s rapping. Paul and I danced together and cheered on the incredible scene we were watching, the whole bar coming alive at these two making music together on the spot. What was more unexpected, though, was running into the same genius freestyler Ewald in Ometepe, where we joined Challis and Fanny at Zopilote, a permaculture farm on the rural side of Ometepe where we extended our stay for a week and settled down into paradise. The farm-hostel was a hippie haven, where cacao ceremonies, fire shows, wood-fired pizzas, home-picked starfruit, and stargazing from the jungle mirador were daily occurrences.

As well as our new group of friends living or staying in Zopilote, we were joined by Pipo, a good friend of Lukas’ back in Germany. A newcomer to hostel life, he took some time to get used to the giant spiders who’d made our jungle cabin their home, and the basic simplicity of the facilities here, in this tiny little corner of the world. But I was in love. With it all. With the small outdoor kitchen, or “kleine kuche” as we fondly named it, with the daily picking of starfruit to add to our porridge or mismatch meals that we’d share with passers by, with the walk up through the side of the volcano to our beds, with the nature and the beauty that co-existed here.

But as always with me, things go wrong, a lot. This time, it was really bad. On a drive back from Playa Mangos, our sunset hang-out spot, Paul and I fell off our moped on a dirt road, and despite him trying to pull me onto my side to avoid injury, it was inevitable. Immediately after the fall I took very slow, deep breaths to stop myself having a panic attack, and the next thing I knew, after screaming “mas agua!” at the local woman gushing water over my mangled knee, I was on the back of a motorbike clinging on and trying not to pass out from the pain. The locals had rushed to our aid instantly, taking me to a local healer woman in a back-yard pharmacy who cleaned my wounds as best as she could. I laughed and compulsively tapped my unhurt foot on the ground through the pain, repeating “be brave, Cerys” in my head as she scrubbed my knee and my elbows and my hand and my foot. A little boy watched with a phone flashlight on the injuries through the darkness, looking worryingly up at me and back down at the horrible bloody mess that he shouldn’t have been witnessing. The woman told me I was incredibly strong, that others would scream in pain where I just blinked away tears and smiled at the boy. It’s funny, but in that moment I felt so alive. This was real pain, waking me up, making me completely understand my body’s ability to keep going. Paul arrived shortly afterwards on the back of a motorbike to get cleaned up, and while his wounds were much less deep than mine, he looked into my eyes as the woman turned to wash away the dirt in his leg, and we smiled at each other. We were strong. We were a team.

And we were the best team I’d ever known. I remember reading adventure and action books as a teenager and creating a dream that one day I would be as strong and brave as the female protagonist, that one day I would meet someone who was just as brave and strong as me and that we would just work together. And as Paul and I sat in our cabin, peeling off gauze to re-dress and re-clean our horribly black wounds, it struck me that this was it, this was me living my dream. Obviously I hadn’t dreamed of falling off a moped and being put out of action for weeks, potentially having to go home abruptly because of it, but the way we laughed and grimaced and shined flashlights on disgusting gashes in each other’s skin felt like a dream, a dream I’d been waiting a long time for. Maybe it was the shock or the painkillers deluding me into romanticising it, but I felt more powerful than ever before. I was so proud of myself, of us, so alive and bold.

We begrudgingly extended our stay in Zopilote again so I could regain my strength, and I started going to the public health clinic in the local town Balgue to get my injuries scrubbed and re-dressed every day. Every day, I woke up early, walked down through the jungle to the main road, hitch-hiked or caught a bus into town, endured the pain for an hour, and then hitch-hiked and walked back up to the hostel, only being able to pass out from exhaustion after the whole ordeal. It was the worst pain I’ve ever experienced in my life, and it was relentless. Every day I hoped it would be quicker, easier than the day before, but every day it was the same, sometimes worse. First the nurses would peel off the excruciatingly stuck bandages off my skin, then use soap solution to scrub wounds all over my body, then water to wash it off, then a scalpel to dig out pebbles buried deep in flesh, then antiseptic spray, then antibiotic cream, then dressings again. It was the longest hour of every day, no anaesthetics, sometimes just a table for me to lie down on if the pain was too much, but I was strong. I would blink away single tears from my eyes, silently screaming as the scrubbing intensified, staring out of the window motionlessly, whispering affirmations in my head. Be brave. Be strong. Come on.

The nurses were very kind, and I felt like they liked me. There was a group of them and they each had a turn examining my wounds, patching me up. The service was completely free, as per Nicaragua’s surprising healthcare system, and while it was by no means NHS-approved, I was just immensely grateful for them making sure my wounds were kept clean, out of the goodness of their hearts. They didn’t have to tell me to return every day, but every day they did, and every day we tried a little bit harder to get the dirt out of the deep gash in my knee. It would leave a permanent scar, a big one, and I knew that, but I didn’t mind all that much. It was a reminder that I sat here, in this pink cement building that’s only usually used to weigh babies, in a foreign-speaking country on the other side of the world, with completely inadequate equipment, able to conquer this pain. Mostly Paul came with me to the clinic, and he wasn’t afraid of seeing wounds or seeing me in pain. He was actually fascinated with the healing process, and he watched the nurses peel off old dressings, examining changes in the wounds with them. He didn’t try to hold my hand or tell me everything was okay; he knew I could handle it, so instead he sat on the chair and watched me wriggle through the pain, smiling at me when I looked at him. We said nothing, because there was nothing to say. Just accept, and stay strong.

During this time I was able to see both Challis, who I’d missed immensely since leaving Guatemala, and Jan, who I’d volunteered with in Costa Rica and who’d met Paul and Lukas in our harmonious week of pura vida. Each reunion was horribly bittersweet, constantly reminding me of my current weakness as I had to turn down climbing a volcano, beach parties and pizza nights. Where I’d usually be thrilled to have so many of my favourite people miraculously in one place, I was overcome with a sense of entrapment – I was stuck in the hostel, stuck with a very large group of German natives who’d often forget I was there, stuck holding back my friends who constantly had to check in with me, infuriated at even being there. Sometimes I wanted the ground to swallow me up and propel me to the safety of home, Bournemouth, instead, where I knew I’d inevitably have to go soon due to my dwindling money and poor physical health. But going home was escaping the pain, entering a comfort zone, being able to see a real doctor and waiting for the next boring year of my life. No, I thought. The world is my home now. I can’t run away from it.

And so I made my last impulse decision, my last crazy adventure on this whirlwind ride of a backpacking experience. Jan, Pipo, Paul, Lukas and I sat in a new hostel on Ometepe, smoking cigarettes and watching the sun go down, discussing our options. A Nicaraguan coin sat on the table in the middle of us, on one side an old, important looking man, and on the other, the volcano, sun and lake which appeared on the country’s flag. The coin was flipped, and as the silver volcano glinted in the day’s fading light, we all muttered together. Corn Islands. It was the side for the Corn Islands, on the Caribbean side of Nicaragua, two days’ journey away. My insides tightened, with fear or excitement I wasn’t sure, and I exhaled, laughing. “Okay, let’s do it,” I said seriously, knowing the decision was already made. The table broke out into celebration, a buzz of new plans and adventures spreading into the night, and this chaotic universe made sense again. Fuck it.

That was, until Paul, Lukas and I reached Managua. Initially, we intended the stopover to be for a brief hospital check-up on my leg, to grab some antibiotics and new dressings before getting on the night bus to Bluefields and reunite with Pipo and Jan. I was not prepared to spend a second longer in Managua than absolutely necessary, given my last escapades in this horrid capital city losing my phone at night. But Paul managed to contract an awful illness and serious fever, ending up in hospital overnight with a kidney infection that delayed all our plans. I acted as translator as well as nursing my deep, infected leg, almost imploding from stress while staring into various nurses’ eyes pleading that they’d just speak a bit goddamn slower so I could have a hope understanding them with my dodgy Spanish. We extended at a hostel after Paul was admitted, stuck in this hateful city once more and only able to wait for Paul to be pumped with fluids in a Nicaraguan hospital, lying on a table in a communal waiting room because all the beds were gone. The hostel was a bizarre, nightmare-induced establishment with an unbearable set of rules, and watched over 24/7 by its creepy owner, an older American guy. For some reason, the city managed to attract the same kind of machoistic, throttle-worthy American guys, all boasting about how much knowledge they had in infuriating monologues and competing against each other over nothing.

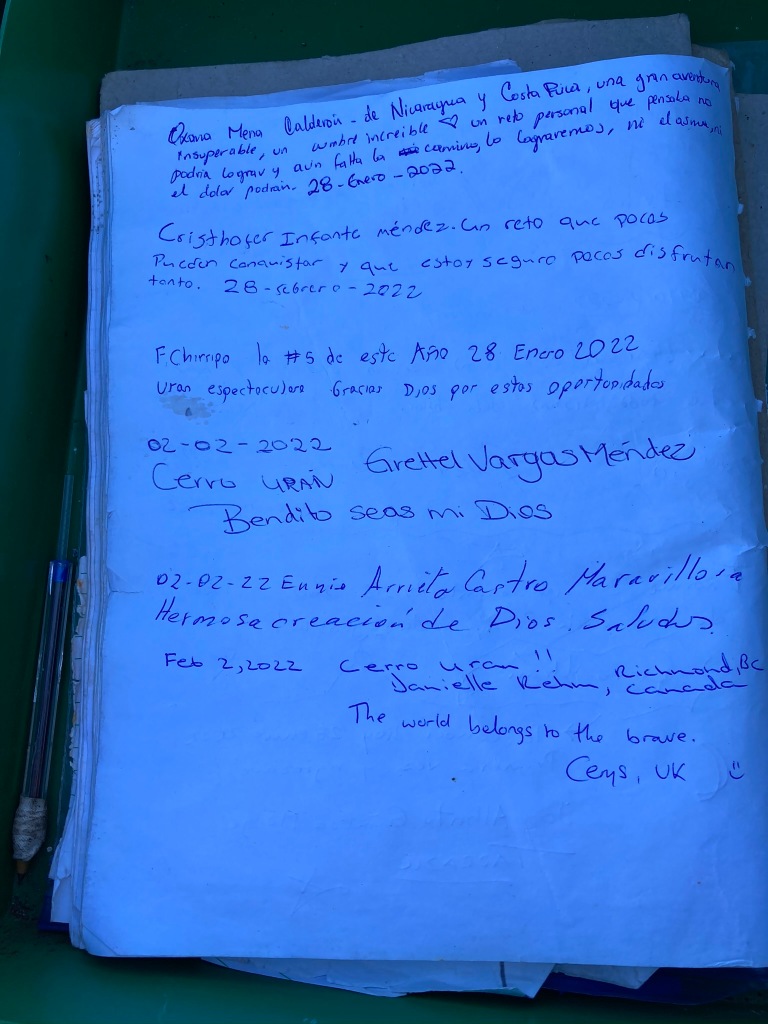

A day after Paul returned from hospital and rested off the worst of the infection, I drew the line. I didn’t care where we went, but we had to get out of godforsaken Managua. The Corn Islands was looking unlikely, and the only other place we felt happy enough to go to was Puerto Viejo, our home in Costa Rica. Either way, it was two days of travelling, and at this point I was considering just booking the next flight back to London, but Paul chose Puerto, and my heart finally calmed. Yes, of course. So while Jan and Pipo pushed on with the initial plan, our trio, our beautiful chaotic team, headed back to the Penas Blancas border, the border I’d been to at least three times now, back into pura vida land. We drank our final beers before crossing, washed down with a painful $60 taxi to the nearest town Liberia after the buses stopped running, and found a lovely hostel for the night with writings all over the walls which we contributed to.

Smoothly arriving back in San Jose the next day, the only other obstacle left was getting a bus to the south, however this proved to be the hardest, after being horrendously scammed out of $150 by an evil taxi driver who span us a web of lies about catching up with the last bus of the day which had already left. My terrible gut feeling was right, and after escaping the taxi and catching the only bus available to Limon, a horrible place pretty much equalling to Managua, we re-grouped in McDonald’s, the only safe place in the whole vicinity, weighing up our options and internally crying over the scam. We called William, the owner of Hostal Cecilia and our sole potential saviour at 10pm, stuck in a dangerous city hours away from Puerto without a place to stay, and he arranged for a friend to pick us up and take us directly there for a small price, telling us we could stay in the hostel for free tonight for our troubles.

Arriving at the door of Cecilia felt like we’d finally escaped the battle ground, and suddenly the 24 collective hours of travelling, with my deeply wounded leg and Paul’s recovering infection, was all worth it. I almost collapsed into an emotional and exhaustive fit of tears before even entering, and being warmly welcomed by Cecilia, William and their family, we knew we’d made the right decision. We were home.

The only news better than the free night’s stay, in my last blissful week of adventuring, was that Anna would be making a return. Yes, Anna, the crazy German legendary solo female traveller I’d met up with in Mexico and Colombia. She was now making her way up Central America after her South American journey, and would just so happen to be in Puerto Viejo the same week as us. It seemed beautifully poetic that, just as I started my trip by her side, I was ending it with her too. She had single-handedly changed my whole view on travelling, my whole life, really, with her insane spontaneity and lust for adventure. She arrived in town in the shitting rain, and we spent a lazy day laughing together, with me displaying my battle wounds which were still yellowing and grey, as we made food, drank beer and did nothing in particular other than watch the rain. I also found it beautiful that Paul and Lukas were with me during my final week, the people who had undoubtedly impacted me the most other than Anna, and who had brought me more joy than anyone else in the half-year I’d been backpacking. I watched Paul surf, read books, drank beer, cycled to Manzanillo with the others, watched the sunset from the plateau above Puerto, and slowly reflected on what I was leaving behind.

The most obvious and painful thing to leave behind was Paul, who I wouldn’t see now for at least a couple of months. Just as we fell more in love after the moped accident in Ometepe, with pride and strength in each other, when faced with my leaving it grew immeasurably more. We went on small dates, walking to the beach and watching the waves and eating veggie burgers and grabbing coffee and reading together, we talked a lot, we learned more about each other than I thought was possible. I glowed with pride watching him skate, effortlessly dancing over cement like an angel, and he watched with a smile on his face as I nonchalantly sprayed antiseptic on my wounds and re-dressed them myself, which I was getting pretty good at. I’d decided to take up surfing properly at home when I was recovered, itching to move my body and do something that makes me scared to feel alive, and he lit this passion within me with a fire that could only come from him. This was the boy I missed a flight home for, who I took the biggest risk of my life for, who I’d do it all again for.

The other thing I was leaving, which was much harder to comprehend, was, to put it simply, my whole life. Travelling had become my world, packing and unpacking and moving and exploring was my norm. For five months I’d called every new place my home, I’d left behind material possessions all over Latin America, as if they were scattered markers that said ‘Cerys was here’; I’d become so comfortable with the uncomfortable that I had my own chaotic rhythm of moving with the world, like an unsteady heartbeat. But I knew that this was exactly the reason I needed to leave. I was getting too comfortable with the familiarities of backpacking, I was feeling safety in the unknown. To leave, to change, to start again all over again, was a harder, bigger, more important challenge. I couldn’t cry when Anna and I caught the bus away from Puerto Viejo, towards San Jose, the place where everything begins and ends, the bus we almost missed because it wouldn’t be me without some chaos. Everything happened so fast, saying goodbye to Paul, rushing to stop the driver and getting yelled at to hurry up, that I couldn’t process the weight of leaving. So I sat on the bus for hours doing nothing, staring out of the window, thinking about the life I had which had just come to an end.

And so, as always with this silly little solo trip of mine, it was time to start again. Onto the new chapter, the next adventure. Como siempre, the world belongs to the brave.